GDP contracted in Q2 by -0.9% and will ignite a debate about whether or not we are already in a recession. But the real challenge for investors is ahead: The Fed is now significantly more hawkish than markets, and with inflation still troublingly high, is likely to continue to inflict pain on traditional asset valuations.

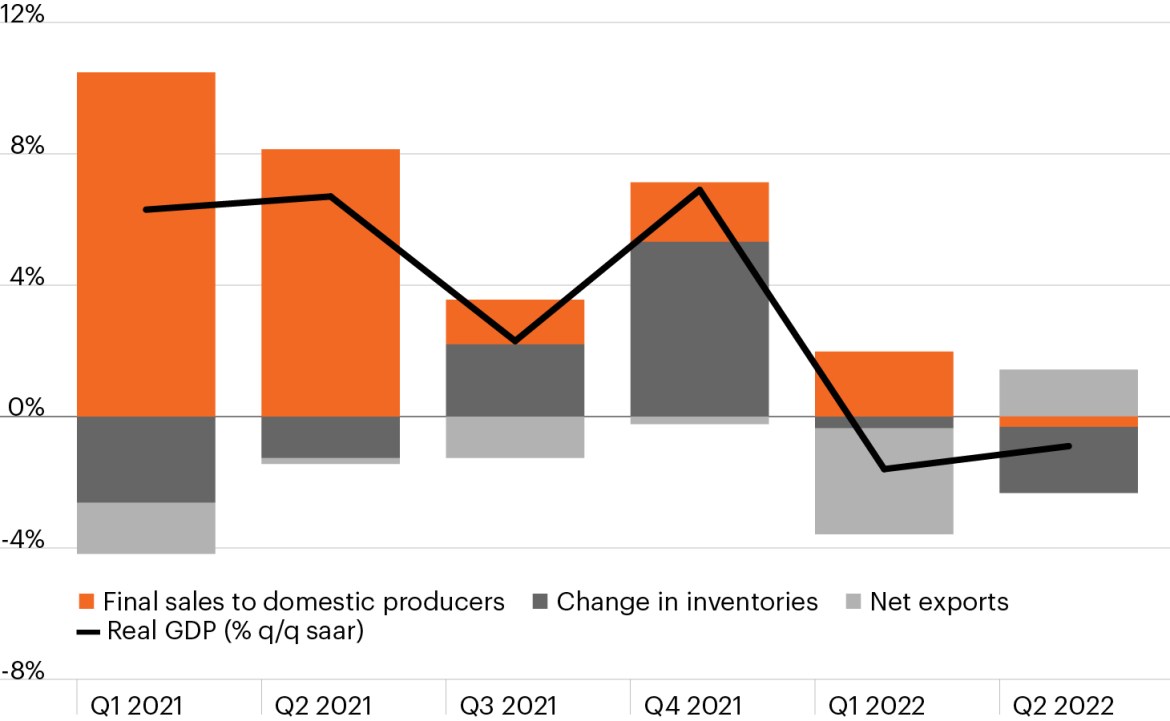

The U.S. economy runs out of gas: Thursday’s report showed real GDP contracted -0.9% quarter over quarter in Q2, a worse-than-expected reading that reflected slowing consumption and outright weakness just about everywhere else. Business investment fell -3.9% with declines in both structures spending and capital equipment, and residential investment (housing construction) plunged -14.0% in the quarter. Household spending rose 1.0% quarter over quarter as a hefty 4.1% in services spending more than offset a -4.4% decline in durable goods spending. The Fed’s rate hikes are doing their part to quash demand. Inventory swings and the trade deficit continue to add enormous noise to the headline in any given quarter since the pandemic began. Zooming in on final sales to domestic purchasers—which is a truer reflection of U.S. economic demand in the quarter—the deceleration from a healthy pace the prior three quarters is painfully clear.

Contributions to real GDP have shifted significantly

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, FS Investments, as of July 28, 2022.

The recession debate of 2022 begins: Are we already in a recession or not? Pundits can—and will!—debate this question ad nauseum. But whether a recession began in February or in June or could begin in September (or even in 2023) misses the big point. The problem for investors is the trajectory of the economy from here is likely further weakness. We have now had two quarters of negative GDP growth, after the headline Q1 contracted -1.6%. And yet our $24 trillion dollar economy cannot be simply distilled into one number. My answer to this debate is: “Not yet.” The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)—the official referees of when a recession begins and ends—look at output, employment, income and industrial activity to establish the start and end of broad-based, pervasive weakness. In contrast to the output data, the employment data have remained strong. The economy added 1.6 million jobs in Q1 and 1.1 million jobs in Q2. In March of 2020, the pandemic caused broad lockdowns and our economy shed 1.5 million jobs in one month—unambiguously marking the beginning of a recession. But that is not typical. More commonly, our economy slips and stumbles in a lopsided manner into a recession, and the referees only call the game several quarters after the official start. In short, expect this debate to add to economic uncertainty for some time.

Does it matter? To me, this debate is a distraction from the challenges that lie ahead for the economy and financial markets in the second half of the year. If we are really in a recession, then we have only seen the beginning. If we aren’t yet in a recession, then the Fed will keep raising rates until they see job losses that cause the unemployment rate to move higher (more on the Fed below). Either way, the economy will be a grind in the second half of the year and economic uncertainty will be an enormous weight on financial markets. Different from the pandemic, this is unlikely to be a V-shaped business cycle. The trajectory from here is likely one of further economic weakness.

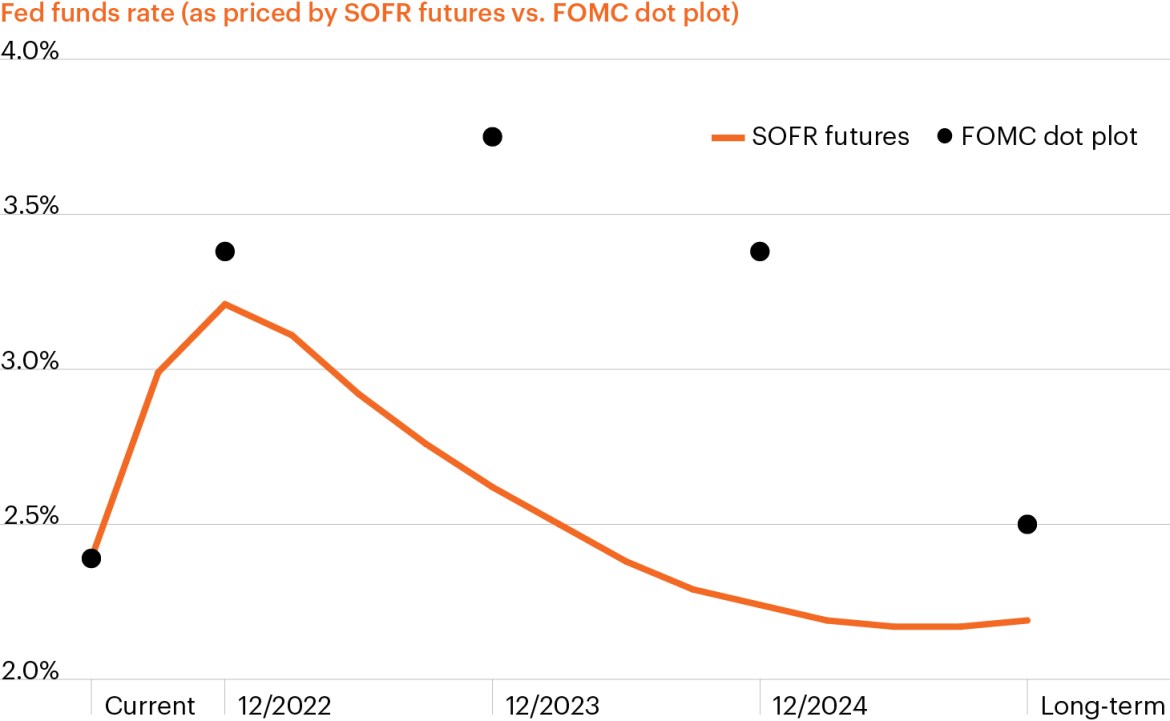

The hawks are still circling: GDP data wasn’t the only action last week. On Wednesday, the Fed raised rates 75 bps to 2.25%–2.50%, as was widely expected. Markets have another 50 bps hike priced at the September 21 meeting and about 100 bps total by the end of the year. The Fed has raced to bring the Fed funds rate into neutral territory. Think of a car: When the Fed funds rate is below neutral, their foot is on the gas. When rates are above, their foot is on the brake. Neutral, which the Fed estimates between 2%–3%, is coasting. After September (assuming a 50 bps rate hike), markets turn more dovish than the Fed and expect an end to rate hikes in 2022, and look for rate cuts in 2023. Fed Chair Powell referred to the dot plot at his press conference yesterday, which includes a further 50 bps of rate hikes in 2023. He also expressed multiple times that the Fed expected to see the job market weaken as part of their strategy to fight inflation.

Source: Bloomberg Finance, L.P., as of July 28, 2022.

What to watch in Q3: Data in Q3 will now be even more closely scrutinized, with a particular focus on the jobs market. We have often highlighted initial jobless claims as the canary in the coal mine for recession and note that initial claims often bottom 9 to 24 months before a recession begins. Claims bottomed in March, but at 256,000 in the week ending July 23, remain at exceptionally low levels. A rise to 280,000 would be a strong indication that the weakening job markets could turn an economic stumble into a fall. We also get two inflation reports between now and the September FOMC meeting. The June inflation report showed price pressures bubbling up more intensely and more broadly than expected. In July, the price of gasoline has fallen 15% since its peak of $5/gallon, and will alleviate some of the most acute energy price inflation. And yet rents—a far larger weight in the inflation index—continue to push higher, ironically driven up in part by the Fed’s rate hikes, which have caused new home construction to slow. A lot will have to go right to get inflation significantly lower on a sustainable basis and allow the Fed to credibly declare victory.

Market reaction: The market rally in the wake of worse-than-expected GDP data has been a classic “bad news is good news” reaction that hinges on the expectation that the Fed will slow rate hikes and cut rates more quickly than expected at the first sign of trouble. The S&P 500 rallied 2.62% after the FOMC announcement and 1.21% after the GDP report. The 10-year Treasury has fallen -13 bps since the latest 75 bps rate hike to 2.67%, the lowest since early April. This reflects both market conviction that we are in or close to a recession, and that the Fed won’t push rates far above neutral. But the Fed has basically done away with forward guidance, another sign that policy will react fast as the data evolve and adds to policy-related volatility in the coming quarters.

Beyond the R-word: The recession-or-not debate can easily distract from the real challenge; the economy is slowing, inflation is higher and traditional fixed income yields are still far below what is required to generate real income. Markets have recently taken comfort that the Fed is closer to the end of their perceived rate hike cycle than the beginning, but persistently high inflation remains a game changer that the markets still have not fully internalized. The Fed has significantly less latitude to cut rates, even in the face of a slowdown, particularly if it is mild. While the traditional markets are mistakenly pricing the same old Fed, investors need to manage their portfolios around both inflation that is likely to remain stubbornly high for the coming year, and economic volatility that is likely to intensify given that meaningful signs of a slowdown are here.