Heightened volatility took its toll on valuations, which corrected sharply lower in the final quarter of 2018. Uncertainty surrounding trade policy, geopolitics and shifting monetary policy has certainly not been constructive for asset prices. However, behind this headline-driven volatility looms a more classic late-cycle profit squeeze that could challenge traditional equity returns for some time to come. Understanding the connection between the business cycle and profits is an important part of investing in the coming year.

The valuations air pocket of Q4

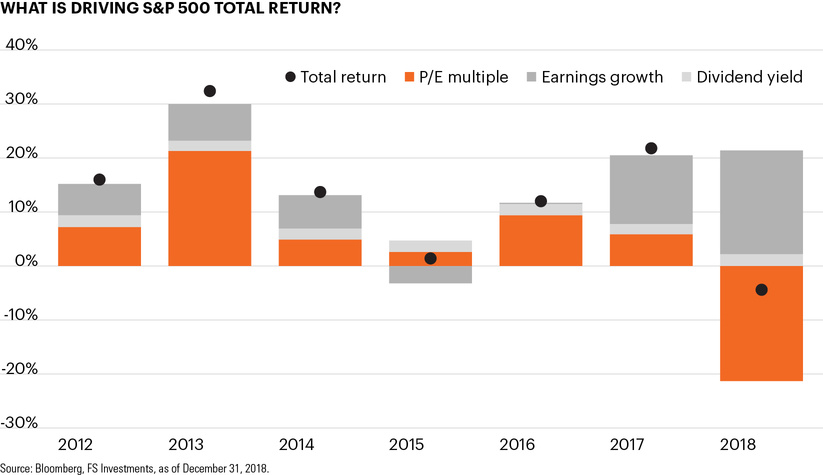

Before we look ahead, it is important to fully understand what drove returns in 2018. Despite earnings growth of 19.2% last year, the S&P 500 Total Return Index fell 4.4%. What happened?

There are three building blocks of total equity returns:

- The most stable component is dividend yield, which averaged 2.0% per year over the past 10 years and historically does not exhibit much volatility. It is often overlooked that this is the only cash that is paid out to long-term equity investors.

- Earnings is often considered the primary driver of returns. Certainly, earnings growth is regularly the focus of financial news and quarterly results as it gives a snapshot of a company’s current bottom line. In fact, earnings growth in 2018 was the strongest we have seen in 8 years. This is in stark contrast to prior years in which earnings growth was significantly slower, or even negative (like 2015), and yet total returns were positive.

- The third driver of total return is price-to-earnings multiples (P/E multiples), which reflect investors’ forward earnings expectations. In 2018, all of the decline in returns was due to the meltdown of P/E multiples, which plunged from 21.8 in 2017 to 17.1 in 2018. Despite this downward correction, the current P/E multiple is not far below the long-run average of 18.7.1

There have been multiple factors affecting forward earnings expectations, including uncertainty around trade policy and continued weak growth data from other major economies. But this significant repricing of forward expectations can be in large part attributed to the late-cycle dynamics of our economy. In other words, even if other geopolitical uncertainty resolves, the late stage of our recovery means we may not return to P/E multiples of the prior two years.

Late-cycle dynamics can squeeze profitability

This year, our economy enters its eleventh year of expansion and is set to become the longest in the post-WWII era.2 There are particular elements of a late-cycle economy that create a more challenging profit environment for companies and heighten volatility. A couple of them directly impact investor sentiment.

Strong labor markets

The first element comes from the positive momentum our economy has built up over 10 years of growth, which has pulled the unemployment rate down. In 2018 the unemployment rate averaged 3.9%, well below the Fed’s estimate of the equilibrium non-inflationary rate of unemployment, which is 4.4%.3 In fact, the U.S. unemployment rate is near its lowest since 1969.4

Strong labor markets may be great news for those looking to switch jobs, but for companies, it often puts upward pressure on labor costs. So far, wage gains have lagged those of prior expansions. Yet wages are starting to accelerate. Average hourly earnings rose 3.1% in Q4, and the employment cost index was up 2.8% in Q3. Both are at cycle highs, though still below the top of the prior expansion.5

Over the past decade, large companies have often relied on cost cutting to bolster profits. This model gets increasingly difficult as the labor market continues to tighten. In the most recent Beige Book, the Fed’s summary of economic conditions for each Federal Reserve district, the Fed noted that “wages increased across skill levels … as firms sought to attract and retain workers and as new minimum wage laws came into effect.”6 Add to this the fact that low inflation and low inflation expectations are working against companies as they struggle to pass through higher costs to consumers. This means that higher employment costs are absorbed by an erosion in profits.

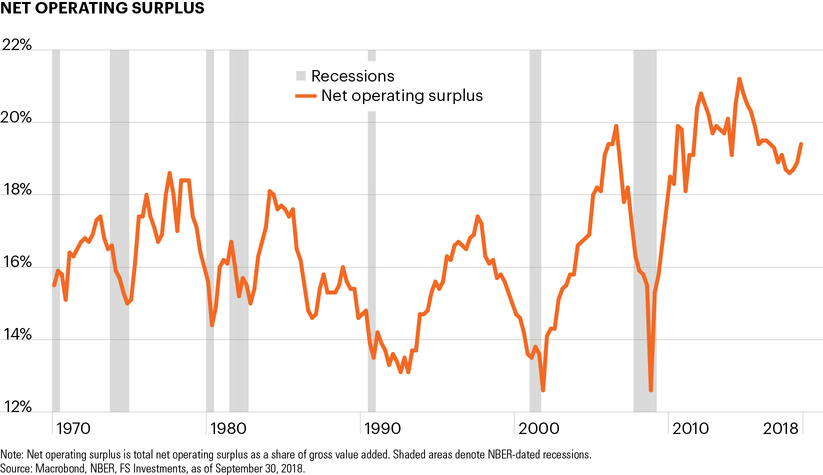

A historic look at net operating surplus – an often-used proxy for profits – bears out the cyclical nature of profits. Late in the economic cycle, GDP growth is often quite strong, but profits are squeezed later in the cycle as costs rise. This does not mean the U.S. is heading into a recession. It does mean that if history is any guide, the peak in profits for this cyclical expansion is likely in the rear-view mirror. In 2018, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act gave the net operating surplus an updraft by lowering the tax burden faced by corporations. Since this legislation is unlikely to be repeated, the improvement in profits is likely to prove fleeting.

Evolving monetary policy

Another typical challenge to late-cycle economies is a tightening in monetary policy conditions. As we saw at the end of last year, Fed rate hikes can significantly heighten uncertainty. After raising the Fed funds target band to 2.25%–2.50% amid amplified market volatility, the Fed indicated that the low inflation profile of the U.S. economy warranted a pause in the tightening cycle.

Yet it is premature to call an end to this rate hike cycle, particularly as wages are creeping higher. The fact remains that one of the most significant late-cycle challenges that companies face is broader economic uncertainty, and Fed policy is often its primary driver. Recessions dating back to the 1960s have been preceded by Fed rate hike cycles. We don’t forecast a recession, but to say that raising interest rates and effecting a “soft landing” for the economy is tricky would be an understatement. We may not have seen the last of monetary policy-driven volatility and uncertainty.

Equities are sailing into return headwinds

No one can predict the future. But of the three drivers of equity returns, two of them could well be sailing into headwinds. Earnings growth is tied to broad economic growth, which is widely expected to moderate in the U.S.7 Growth in the rest of the world is also decelerating,8 a factor which heavily impacts large-cap U.S. companies that dominate the S&P 500 and traditional exchange-traded funds.

Perhaps the most difficult to predict and volatile driver is P/E multiples, which essentially capture expectations of future profits. These expectations are highly susceptible to uncertainty spurred by trade headlines, geopolitics and monetary policy. There is a case to be made that P/E multiples have fallen too far, and expectations can recover quickly. Volatility, however, is likely to hamper traditional equity investments throughout 2019.

The bottom line is that policy uncertainty may be causing heightened volatility, but the erosion in P/E multiples in 2018 needs to be put in a broader context. The dynamics of the late-stage economic expansion stand to squeeze profits from both sides, with weaker revenue generation and rising costs.

Equity investors may find the valuations air pocket at the end of 2018 was not just a temporary rough patch, but the beginning of what could be a more extended period of challenged profits and heightened volatility for traditional equity investments.