The economy starts the summer before the election with healthy momentum and maximum optimism priced into market valuations.

Looking ahead, we expect growth to moderate and inflation to remain stubborn. Monetary policy uncertainty will likely intensify, and regulatory, trade and budget deficit policies are all up for grabs, testing investor complacency.

Key takeaways

- We expect an incremental slowdown in Q3 GDP growth and are watching the labor market closely.

- We look for one rate cut in Q4, as policymakers choose data dependence and patience.

- As the election nears, we expect market volatility to increase notably.

I like to start my quarterly outlook with an overarching theme connecting the economy and markets. At midyear, this connection is the maximum optimism for economic growth that is priced into markets—and how this confidence leaves markets vulnerable to any slowdown in growth, however incremental. The first half of the year was defined by a strong economy that once again far exceeded lackluster expectations at the beginning of the year. In January 2024, markets were expecting growth of 1.3% for the year. At midyear, growth has maintained a solid trajectory. In Q1, real GDP grew 1.3%, but excluding inventory and trade swings, domestic demand growth was 2.5%. Early estimates for Q2 are 3.0%, and personal consumption in Q1 was 2.0% versus 2.7% in 2023.

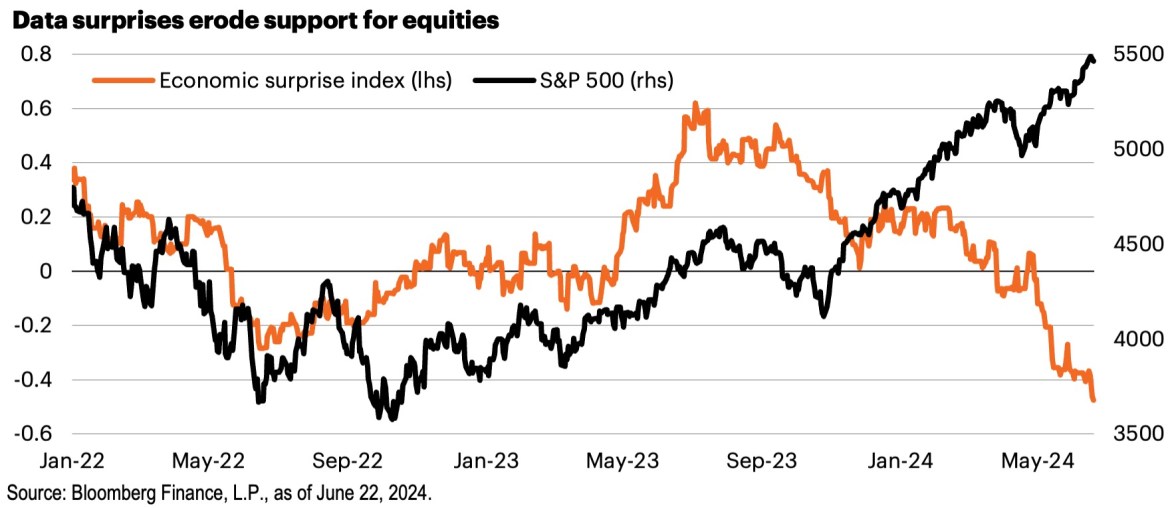

Today, market expectations around growth have arguably done an about-face to reoriented toward a strong economy. At midyear, markets expect real GDP growth of 2.4%, and analysts expect double-digit earnings growth for the next two years. While this backdrop of sentiment can only be described as maximum optimism, markets are starting to see something they haven’t seen in some time: A wave of downside surprises in data. Over the last month, while equities have continued to race higher, the data have broadly disappointed versus expectations. Markets have skated past these data misses with growing complacency precisely because conviction is concerningly high that growth will stay strong far into the future, with no slowdown whatsoever.

Slower growth, better balance and stubborn inflation

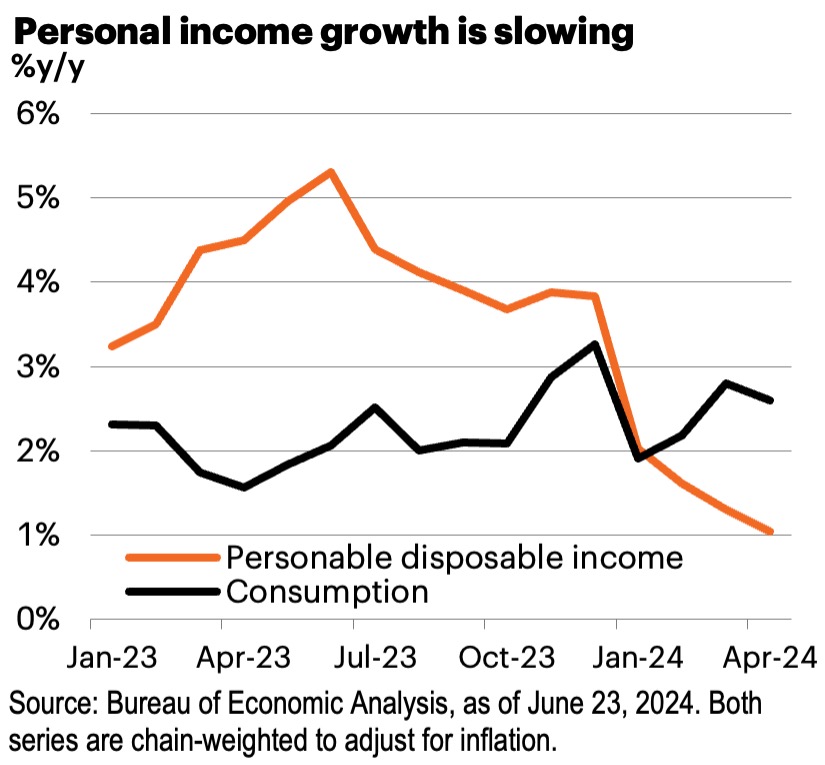

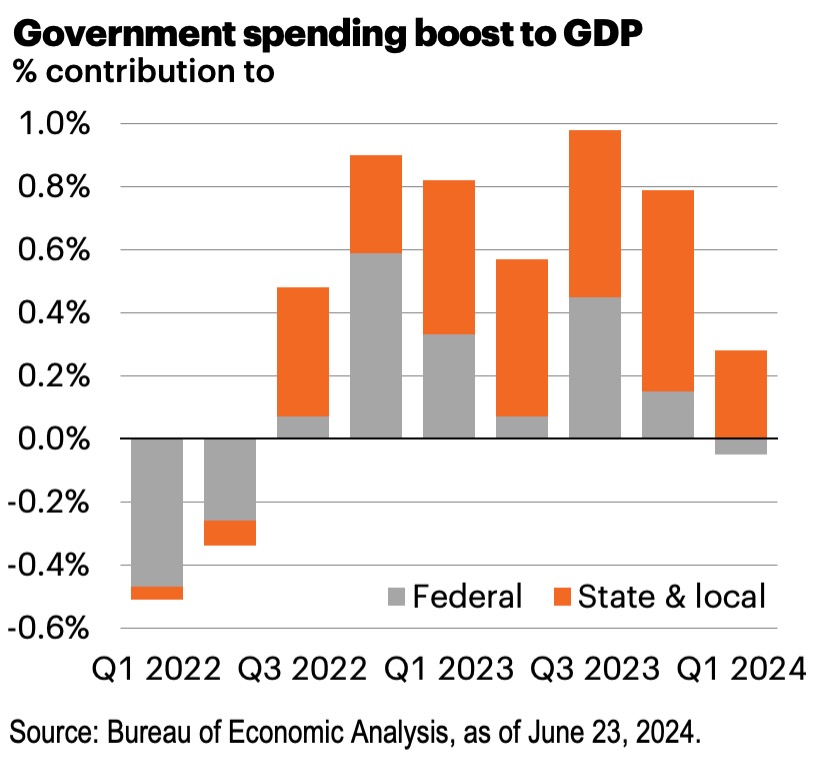

This is the backdrop for the third quarter. The consumer is the big engine that drives the economy, and the labor market remains a solid foundation of support. However, pandemic savings are largely exhausted, leaving consumption growth highly dependent on income growth, which has started to slow. Government spending has also been a powerful contributor to economic activity. The contribution to GDP has been significant, adding 8-tenths to growth in 2023 and 3-tenths in the first quarter. Government activity isn’t limited to expenditures, as government hiring has also been strong for some time, and so far this year has accounted for 20% of the 1.3 million new jobs reported in the establishment survey. Looking ahead, we expect government spending to continue to fade in the second half of the year to a small positive or neutral, which will help growth decelerate from 2.5% to closer to 2.0%.

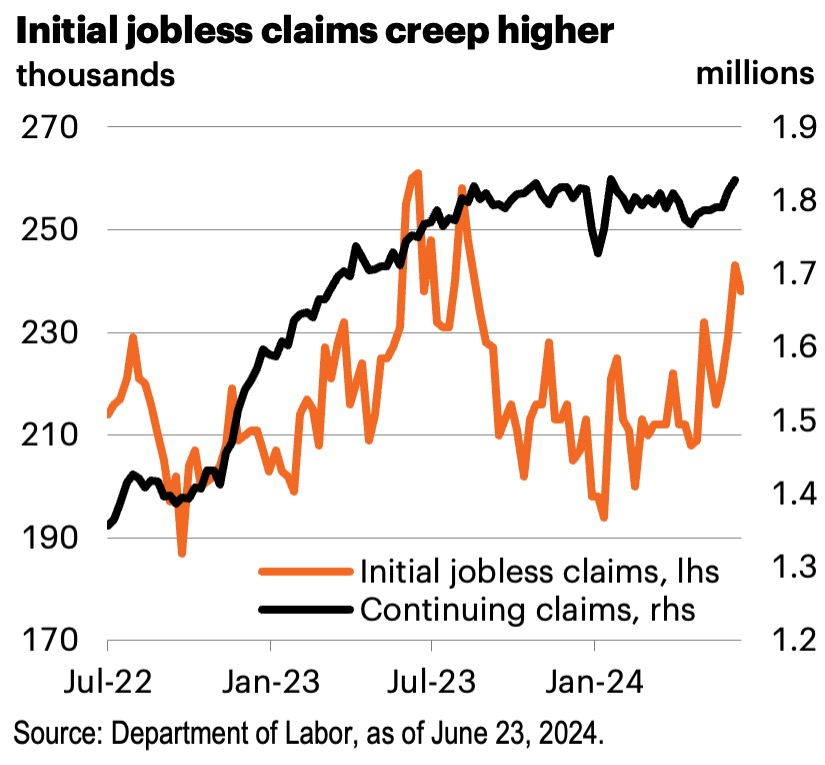

In Q3 we expect the labor market to continue its renormalization from the COVID disruption that caused so many indicators to hit—and linger at—all-time highs. This process is already underway. The unemployment rate has gently drifted up to 4.0% in May from a low of 3.4% in April of 2023. The JOLTS measure of job openings has moved closer into balance, with a May reading of 8.06 million solidifying a steady downtrend back toward the pre-pandemic two-year average of 7.13 million. It is critical not to interpret any of this as weakness in the job market. We are watching our favorite indicator of labor market health—initial jobless claims—like a hawk as it has recently edged higher. It is a weekly series that is choppy, but a reading closer to 280,000 would be a warning sign the labor market may start to actually cool. The unemployment rate is notoriously asymmetric, meaning it historically shoots higher instead of rising slowly. From a policy standpoint, there is a case when looking at the unemployment rate that the Fed has effectively achieved the rare soft landing.

Inflation completes the outlook for the economy in Q3, and our view is unchanged: Inflation will remain stuck around 3% for the second half of the year. Inflation has moved lower since the acute readings of mid-2022, but the path has been choppy and uneven, and the pace of disinflation is slowing. We have long been saying the final leg down from 3% to 2% inflation will be the hardest. We detail our higher-than-consensus expectation for inflation, and why stubborn inflation will limit the Fed’s room to cut rates as aggressively and programmatically as markets expect.

Countdown to the election

The November 5 election is already grabbing the attention of markets and investors. The June debate was earlier than any televised presidential debate in history, and campaign seasons grow longer and longer. The economic backdrop for the election is a surprisingly resilient economy that will likely see real GDP slow modestly in the second half but come into better balance with inflation still a lingering problem.

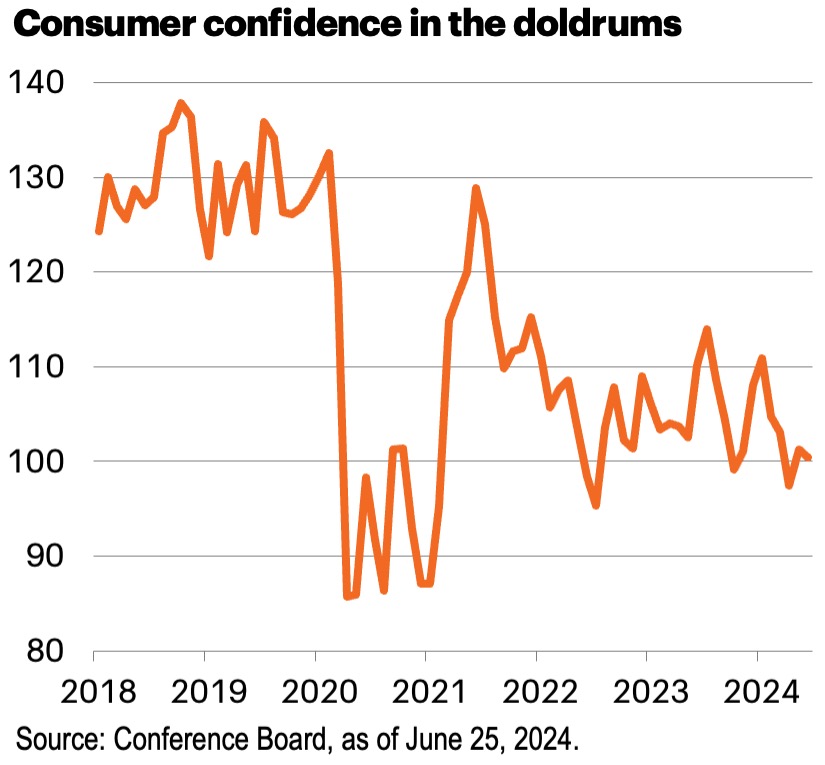

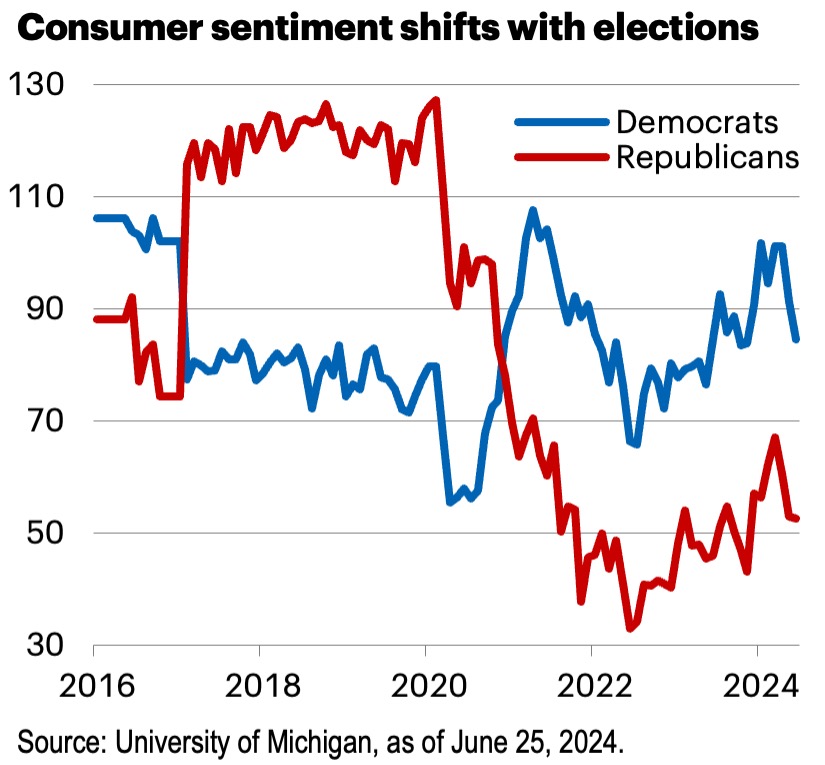

This fairly constructive view of economic growth is at odds with most polling on the economy, which is broadly downbeat. Consumer confidence has remained in the doldrums since the pandemic, and despite growth and employment being as strong as 2018–2019 levels when confidence was much higher. The picture is further clouded by a partisan lens. The economy, as a rule, does not shift quickly, but household’s view of the economy does shift quickly, depending on party affiliation. It isn’t just consumers that are downbeat—the Small Business Optimism index has been treading at multiyear lows.

Two obvious culprits are likely the cause of economic gloom. The first is inflation. The rate of inflation has come down significantly, but the inflation sticker shock is still a clear and present pain point for every household budget. The price of groceries (food at home) is up 21% since the start of 2021, and car prices are up 20%. The Consumer Price Index is up 21% since January 2020. Most voters do not consider inflation enough to differentiate that inflation trending lower means that prices are still going to go up—just at a slower pace—and are not actually falling.

The second is housing affordability and availability. The rapid swing in mortgage rates from just below 3% to over 7% caused affordability to swing to the worst in 40 years. It has also frozen many homeowners in place with low fixed-rate mortgages, crushing supply. In many markets, even if a prospective buyer has the money to purchase a home, there is simply no inventory. At a national level, the number of homes on the market continues to be near the lowest on record. Neither of these factors are likely to improve much before the election.

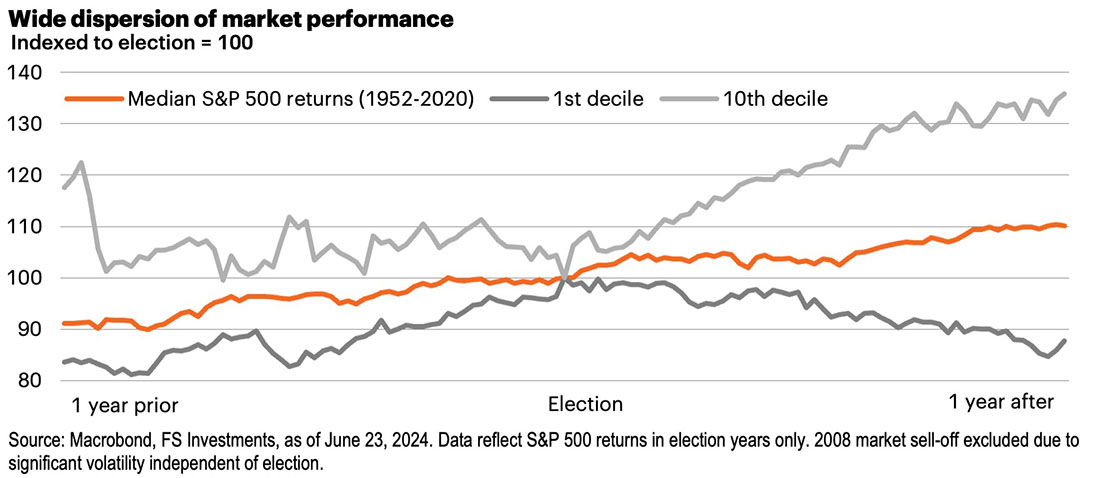

It is difficult to sift a clear macro-market conclusion from election results. Both parties have been in power through bull markets, sell-offs and corrections. There is evidence that markets typically underperform in the months leading up to the election versus non-election years, and later make it up once any uncertainty around the election has cleared. And yet, at no time have we entered an election with market valuations at current levels.

Investors search for patterns in election results

The key observable pattern around election is that volatility rises in the months leading up to election day, in both equity and bond markets. In our article on the election, we note that the volatility in 2020—an election which uniquely featured the same candidates—was significantly higher than the normal pre-election market jitters. We break down key policies that will be up for grabs, including taxes, regulation and trade policies.

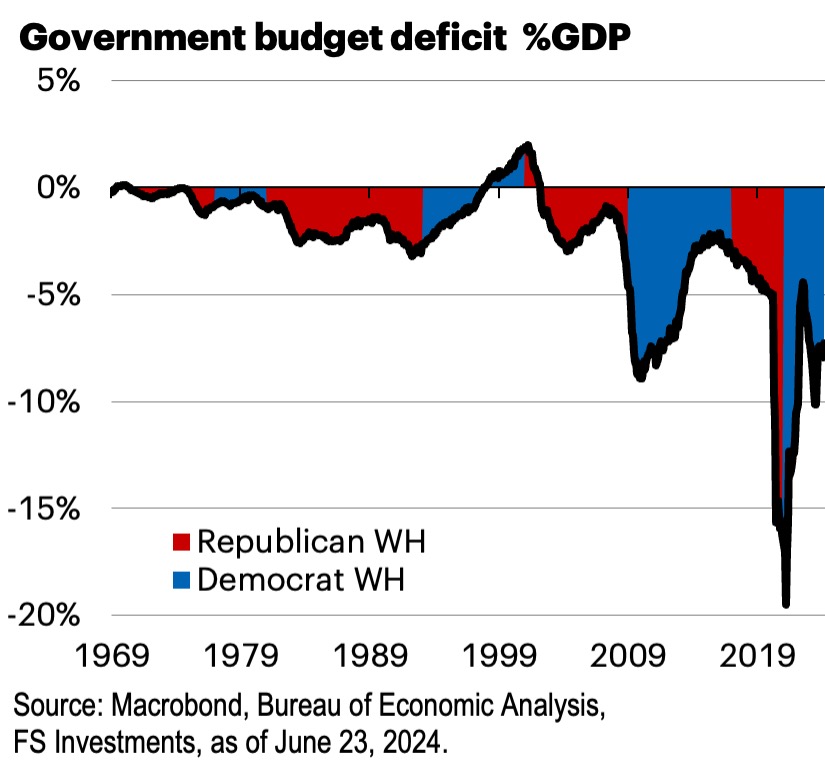

Investors are also increasingly focused on debt and deficit dynamics, although we would argue this is far greater than an election issue. Throughout decades, across administrations of both parties, the country has almost always run a budget deficit. This bad habit has led to the accumulation of $33 trillion dollars of debt outstanding, or almost 125% of GDP. In short, the budget is everyone’s problem, and will take everyone working together to find a solution.

In 2023, the Treasury spent $658 billion on interest payments. In 2024, that number is projected by the Congressional Budget Office to rise 36% to $892 billion. And in 2025, interest payments are expected to be over $1 trillion. Already, interest payments have overtaken defense spending. Financial markets seem to be largely ignoring the long-run implications of debt and deficit dynamics, which include higher interest rates and less room for counter-cyclical fiscal response. We include an article detailing the scale of the issue and where to go from here.

Market optimism will face challenges in Q3

Despite a healthy economic backdrop, markets face some challenges in the coming quarter. Primarily, so much optimism is built into the implied market outlook that any downside surprise could hit performance. In the fixed income market, markets have interpreted the end of the Fed’s rate hike cycle as a green light to pile back into duration because long-term interest rates usually fall when the Fed cuts rates. However, this misses a key differentiator of this cycle: Without a recession, the Fed is likely to move gradually to reduce rates. A healthy economy should, at some point, cause the inverted yield curve to renormalize. We expect more of a twist, with long-term rates trading in a wide range and likely retesting 5% sometime in the second half of the year. Investments in traditional fixed income have returned nothing over the past five years, and could be vulnerable to market complacency where rates are naturally headed lower.

Finally, we end where we started, with expectations. Equity market earnings expectations are for double-digit returns over years, not just over quarters. Valuations reflect this with the S&P 500 trading at over 20x forward price-to-earnings (P/E). In other research, we have discussed intensifying problems with high concentration within the broader index that has stretched to the highest on record. In the third quarter, volatility is likely to pick up ahead of the election. And we expect the economy to mildly underperform high expected growth. When peak optimism is the market’s base case, any other outcome suddenly becomes a challenge