Key takeaways

- Congress is under surmounting pressure to address the debt ceiling before the Treasury hits the X-date, likely late July to early August, and trips into a technical default.

- The 2011 debt crisis exemplified how painful this exercise can be for the economy and markets.

- Despite parallels to 2011, the current backdrop in both politics and markets poses a new set of challenges.

- While various alternatives will likely be floated in the coming months, we believe the only viable solution is for leaders to negotiate a political solution to raise the debt ceiling.

Budding debt ceiling concerns are already clouding the outlook and will likely intensify heading into summer. We summarize the key issues for the economy and markets, look at what is priced in and examine the narrow path to a timely resolution. The range of outcomes is wide, with little room for complacency.

The debt ceiling is back. Like a reboot that no one asked for, the debt ceiling threatens to monopolize airtime this summer. Here is our spoiler alert: We expect Congress to raise the debt ceiling. But there is a significant risk we stumble into a technical default because of a political miscalculation among negotiators and their incentives. Even if this is short-lived, it could have serious consequences for financial markets which could ripple through to the economy.

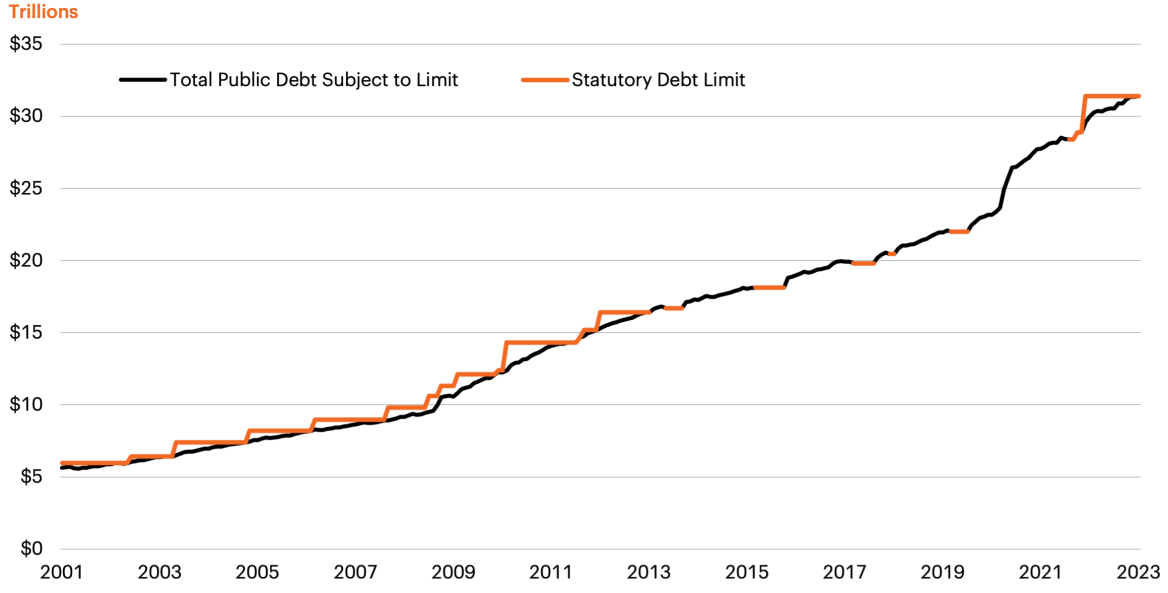

The debt limit reflects procedural changes (made after World War I) that impose an aggregate limit on what the Treasury may borrow—a statutory debt limit that has been raised or suspended 78 times by Congress since 1960. Importantly, the debt limit does not restrict Congress’ ability to enact new spending and revenue legislation that affects the level of the debt. Instead, it restricts Treasury’s authority to borrow to finance the decisions already enacted by Congress. Put another way, raising the debt ceiling does not increase federal spending. On January 19, 2023, the Treasury technically hit the debt ceiling and enacted “extraordinary measures” to prevent a default and create headroom to manage cash flows during negotiations. The timing of when this will come to a head—unofficially referred to as the X-date—can only be estimated because spending and tax receipts are both uncertain. But the clock is now ticking, and we estimate an X-date of late July or early August.

U.S. debt hitting the ceiling

Source: U.S. Treasury, as of March 3, 2023. Gaps in the data represent suspension of the debt limit.

2011 debt crisis revisited

Lessons from 2011 are painful enough that they are worth revisiting, if only to nudge investors away from complacency. The range of possible outcomes evolving this summer is wide, but when we hear other pundits say that we may “only” get a repeat of the prior episode, we cringe: That was a painful period for investors.

Politically, the situation may sound familiar: A Democrat in the White House, Democratic-controlled Senate and a House that had just flipped from Democratic to Republican control. On May 16, 2011, the statutory debt limit was reached and the Treasury deployed extraordinary measures as congressional negotiations began. That summer, despite much public posturing between the two parties, back-channel communications were opened up between then–Vice President Biden and then–House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, laying the groundwork for the eventual deal between President Obama and Speaker of the House John Boehner.

Several rounds of voting—primarily to stake out each party’s political positions—occurred while negotiations proceeded behind the scenes until the eleventh hour. In 2011, the U.S. avoided a technical default. Congress voted on August 2 to raise the debt ceiling along with a host of fiscal reforms and spending cuts. The fallout continued, however, and on August 5, S&P downgraded U.S. sovereign debt.

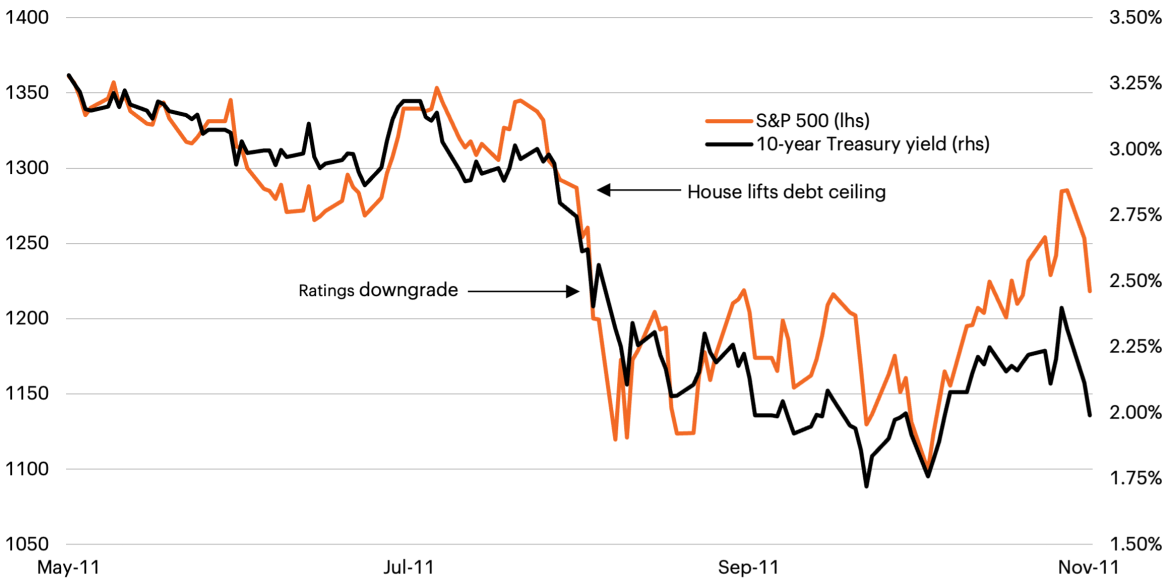

2011 debt crisis was a risk-off event

Source: Bloomberg Finance, as of March 1, 2023.

The ratings downgrade stemmed from two issues. First, “the government’s medium-term debt dynamics,” essentially citing the fiscal situation and growing debt. The second cause for concern cited was “broadly…the effectiveness, stability, and predictability of American policy making.” That following Monday, August 8, the S&P 500 lost 6.7%, the DJIA dropped 5.6% and the NASDAQ shed 6.9%. It took over five months for the equity markets to fully recover. S&P has kept this downgrade in place since then. It is hard to argue that either of the reasons for the downgrade have improved—one could argue they have worsened.

The market reaction was a broad risk-off rotation that ironically caused a flight to quality into Treasuries, despite the fact that repayment risk was the source of the downgrade. The 10-year Treasury yield plunged from over 3.50% in the spring of 2011 to 2.06% in the weeks after the downgrade. High yield spreads shot up from 500 bps in May to 724 bps immediately following the downgrade, and continued to climb for another two months, peaking at 885 bps in October. The VIX jumped from around 16 in May to 48 in August and persisted at over 30 through November.

In 2011, the European debt crisis added to market volatility, but in the U.S. the Fed had just wrapped up its first round of quantitative easing and the Fed funds rate sat at 0.00%, helping to quell market concerns to a degree. Right now, the Fed funds rate is at 4.25%, the Fed is still raising rates and is reducing its balance sheet. At the end of the day, there is no good time for a debt crisis.

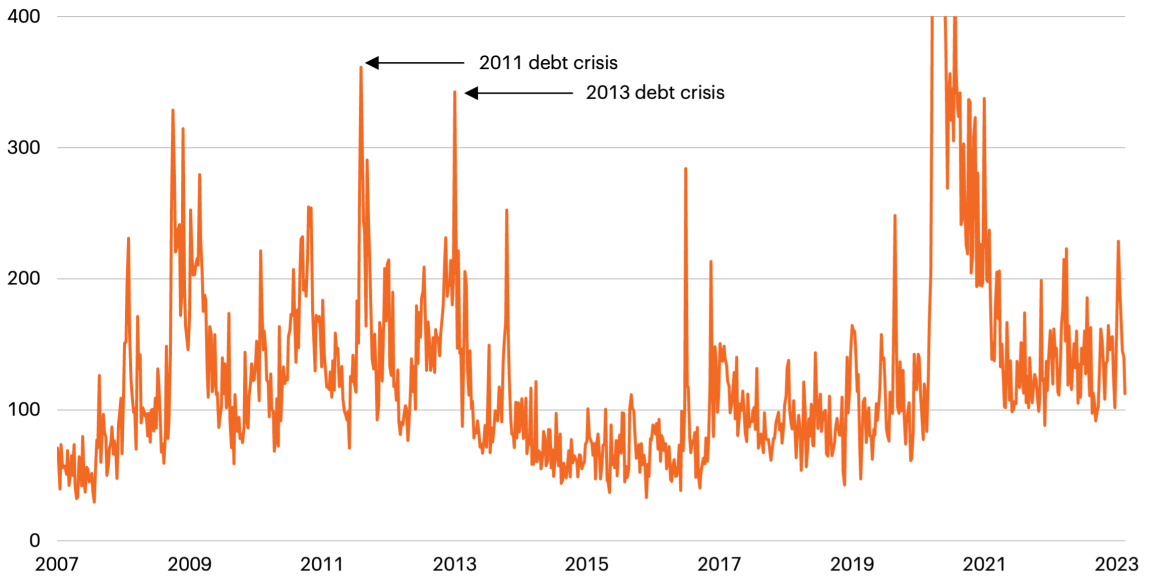

Finally, the 2011 debt ceiling crisis reached into the economy, as well. Economic policy uncertainty was at its highest until the global COVID-19 pandemic. Consumer confidence was staging a fragile recovery after cratering during the Great Recession when it fell from 59.2 in July 2011 to 40.9 in October 2011, the second lowest level of the last 40 years. It is hard to quantify the impact this had on final consumer spending or GDP data, but clearly the debt ceiling debate is more than just a financial market event.

Economic policy uncertainty index

Source: Baker, Scott R., Bloom, Nick, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, as of March 2, 2023. Y-axis truncated due to COVID-related distortions.

Tough lessons from 2011

There are three reasons why we put a significant probability that the upcoming debt negotiations could once again cause market volatility (at best) and come uncomfortably close to technical default (if not worse).

First, House Republicans currently have a razor thin majority of only five versus the 24-member majority they enjoyed in 2011. If the lesson of sparring with a vocal and determined caucus within the majority was painfully learned in 2011, it was reinforced in January with the historic 15 rounds of votes required to elect Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) as Speaker of the House—the most protracted since 1859. To us, this makes clear that outlier outcomes should not be casually dismissed.

Second, the nature of McCarthy’s speakership injects increased uncertainty into the upcoming debt ceiling discussions. A condition of McCarthy’s election was agreeing to restore the motion to vacate, which allows a single member of Congress to call for what is in effect a vote of no confidence in the Speaker. The debt limit loomed large in negotiations between McCarthy and the small group that opposed him as Speaker. This will dramatically influence how he manages any debt limit standoff with the White House.

Third, one could argue that each side learned different lessons from 2011. Biden, who as Vice President was a key negotiator in the 2011 deal, indicated later that the administration gave up too much to increase the debt limit. House Republicans learned if they hold out long enough, the White House will capitulate. All of this adds up to a backdrop for the coming debt showdown that is already more problematic than in 2011.

Raise the roof?

To us, the only viable solution to avert a default is for congressional leaders and the administration to negotiate a political solution to raising the debt ceiling. Other options will likely be floated in the coming months, none of which we view as particularly viable.

Debt prioritization: House Republicans will likely pass legislation that requires Treasury to prioritize debt payments at the expense of other spending. However, we view this as politically unpalatable. Many Treasury bond holders are foreigners, and it is unlikely either party would want to pay foreign debt holders—Chinese bondholders, as an example—before spending on Americans. Moreover, one could argue that debt prioritization is default by another name, as it implies someone isn’t getting paid.

Invoking the Fourteenth amendment: Often floated as a way for the President to exercise an end run around the debt ceiling, Section 4 of the Fourteenth amendment to the Constitution states “the validity of the public debt of the United States…shall not be questioned.” The thought is that by invoking this, the President can just order the Treasury to pay the debt. Yet this is already hotly debated among legal scholars, some of whom claim this runs contrary to Congress’ Article I, Section 8 powers of the purse, and would likely be immediately litigated. In other words, this option could still hold the full faith and credit of the government in legal limbo.

Trillion-dollar coin: This implausible suggestion stems from the Federal law that allows the Treasury to mint platinum coins (ostensibly for commemorative purposes). Under this idea, a large denomination coin could be deposited at the Fed and help the Treasury raise the cash it needs. This would thrust the Fed into the middle of this political situation, however, which is anathema to their goal of political independence. Fed Chair Powell recently reiterated that the solution to the debt ceiling lies with government and that the Fed “does not have a rabbit to pull out of a hat.”

Discharge petition: Under the rules of the House of Representatives, a majority of House members may sign a discharge petition that excises a Bill from committee making it available for a vote before the full House. This idea is gaining traction among House Democrats who believe there are enough members in the GOP conference that would support a “clean” extension of the debt limit to avert default. Unfortunately, there are a complicated set of rules around using the discharge petition that prevent this from being a viable alternative.

These and other suggestions may lend themselves to thought exercises or legal debate, but for investors, it will be a distraction. The path forward through political negotiation is clear, but far from straightforward. In 2011, both sides acknowledged that negotiation would be necessary. Now, there is only the earliest indication negotiations could be considered. Our primary concern is negotiations get started too late.

Countdown to X-date

Further complicating the landscape for investors is uncertainty around the exact X-date. Estimates for the X-date range from June to November, although our expectation is late July to early August. Tax receipts in April and June will give additional information on what runway the Treasury has before it can no longer service the debt.

Credit default swap rates—in essence, the price of insurance against default—on Treasury debt of less than one-year maturity are already showing acute pricing pressure that is close to the 2011 levels. But for other markets it is hard to say how much concern is priced in. Fed rate hike expectations have downshifted over the last month due to volatility in the banking system with markets now forecasting a pause in Q2. It remains to be seen whether uncertainty related to the debt ceiling and banking system has expedited the end of the rate hike cycle. The Fed will need to balance these concerns with their mandate to be politically independent.

For many investors, micromanaging portfolios around a potentially disruptive event is challenging. The likely reaction to another debt ceiling crisis is a risk off rotation, where equities and high yield decline and developed market sovereign debt yield drop as they are purchased as a safe haven—ironically even U.S. Treasuries. Managing volatility has been a challenge for investors for some time, and 2022 gave a painful lesson of the impact that economic and policy uncertainty can have on returns. In 2023, investors do not seem set to get a break. Right as the Fed nears the end of its rate hike cycle, policy uncertainty is likely to be recast.

Market concerns about debt default have already soared

Source: Bloomberg Finance, L.P., as of March 3, 2023.